Traditional Emergency Medicine Practices Can Win Contracts by Thinking Like Lawyers

How EM practices owned by their physicians can thrive using attorney-like strategies of defense and prosecution.

How many of your attorney friends work in a law practice owned by a non-lawyer? The likely answer is “none”. How many of your physician friends work in a medical practice owned by a non-physician? The likely answer is “most”.

As medicine has become increasingly corporatized - with physician practices owned by Amazon, Walgreens, UnitedHealth | Optum, Blackstone, and other non-medical corporate entities - both physicians and the lay public are rethinking whether such arrangements are appropriate. A recent survey showed that “almost 60% of physicians who practice as employees of hospitals and other corporate entities say that non-physician practice ownership results in a lower quality of patient care.” Emergency medicine having both the lowest rate of practice ownership and the highest burnout rate in the house of medicine is likely not a coincidence.

Traditional emergency medicine practices have a problem - they are not winning enough hospital contracts. When American Physician Partners ceased operations in July 2023, the employers that picked up most of the 125 available emergency department staffing contracts were TeamHealth, Community Health Systems, US Acute Care Solutions, and SCP Health.

EM groups owned by their practicing clinicians face the challenge of not being able to open a new emergency department due to certificate of need laws and federal regulations. Emergency medicine groups must win contracts from hospital CEOs, who are often not physicians. Traditional emergency medicine practices need new strategies to win ED contracts at higher rates.

A potential winning strategy is for doctors to start thinking like lawyers. Yes, that sentence sounds crazy. Clinicians spend much of their professional lives trying to avoid malpractice lawsuits. Lawyers are medicine’s kryptonite! Desperate times call for desperate measures.

“Thinking like lawyers” would entail elements of defense as well as prosecution. On the defense side, the the American Bar Association (ABA) protects lawyers from non-attorney ownership. Per the ABA, “The practice of law is a profession, not merely a business. Clients are not commodities that can be purchased and sold at will.”

The American Bar Association’s Rule 1.17: Sale of Law Practice:

Client-Lawyer Relationship

A lawyer or a law firm may sell or purchase a law practice, or an area of law practice, including good will, if the following conditions are satisfied:

(a) The seller ceases to engage in the private practice of law, or in the area of practice that has been sold, [in the geographic area] [in the jurisdiction] (a jurisdiction may elect either version) in which the practice has been conducted;

(b) The entire practice, or the entire area of practice, is sold to one or more lawyers or law firms;

(c) The seller gives written notice to each of the seller's clients regarding:

(1) the proposed sale;

(2) the client's right to retain other counsel or to take possession of the file; and

(3) the fact that the client's consent to the transfer of the client's files will be presumed if the client does not take any action or does not otherwise object within ninety (90) days of receipt of the notice.

If a client cannot be given notice, the representation of that client may be transferred to the purchaser only upon entry of an order so authorizing by a court having jurisdiction. The seller may disclose to the court in camera information relating to the representation only to the extent necessary to obtain an order authorizing the transfer of a file.

(d) The fees charged clients shall not be increased by reason of the sale.

The ABA further clarifies, in Rule 5.4: Professional Independence of a Lawyer:

Law Firms And Associations

(a) A lawyer or law firm shall not share legal fees with a nonlawyer, except that:

(1) an agreement by a lawyer with the lawyer's firm, partner, or associate may provide for the payment of money, over a reasonable period of time after the lawyer's death, to the lawyer's estate or to one or more specified persons;

(2) a lawyer who purchases the practice of a deceased, disabled, or disappeared lawyer may, pursuant to the provisions of Rule 1.17, pay to the estate or other representative of that lawyer the agreed-upon purchase price;

(3) a lawyer or law firm may include nonlawyer employees in a compensation or retirement plan, even though the plan is based in whole or in part on a profit-sharing arrangement; and

(4) a lawyer may share court-awarded legal fees with a nonprofit organization that employed, retained or recommended employment of the lawyer in the matter.

(b) A lawyer shall not form a partnership with a nonlawyer if any of the activities of the partnership consist of the practice of law.

(c) A lawyer shall not permit a person who recommends, employs, or pays the lawyer to render legal services for another to direct or regulate the lawyer's professional judgment in rendering such legal services.

(d) A lawyer shall not practice with or in the form of a professional corporation or association authorized to practice law for a profit, if:

(1) a nonlawyer owns any interest therein, except that a fiduciary representative of the estate of a lawyer may hold the stock or interest of the lawyer for a reasonable time during administration;

(2) a nonlawyer is a corporate director or officer thereof or occupies the position of similar responsibility in any form of association other than a corporation; or

(3) a nonlawyer has the right to direct or control the professional judgment of a lawyer.

Simply, if a lawyer sells to a non-lawyer, they would face career-threatening consequences from the American Bar Association.

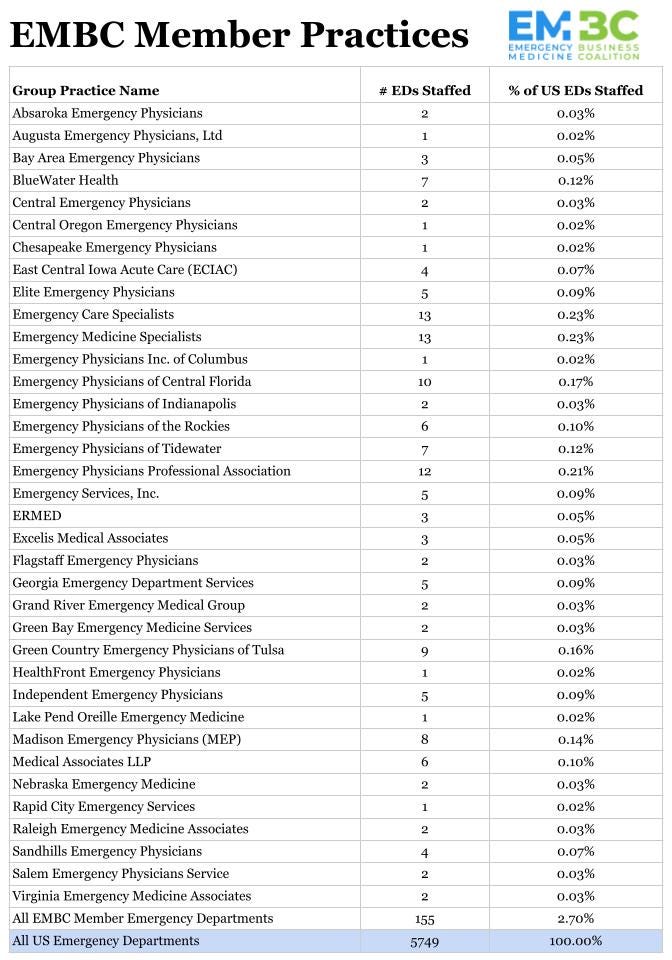

Traditional emergency medicine practices need a clear way to define who meets the criteria for physician ownership. As Howie Mell, MD, MPH, wrote, “When potential employers claim to be ‘physician-owned partnerships,’ can you trust them? The answer, unfortunately, is no. Not every group that claims to be physician-owned gives all doctors an equal voice and vote in practice matters.” Two entities currently certifying emergency medicine practices are the American Academy of Emergency Medicine Physician Group and the Emergency Medicine Business Coalition. Associations, hospital CEOs, and physicians need this information to make informed decisions favoring traditionally structured emergency medicine practices.

The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) has thus far refused to protect physician-owned practices from sale to non-physicians. ACEP’s Antitrust Policy includes language interpreted as not protecting traditional EM practices. This is a choice, not a legal requirement. ACEP has the same legal entity designation as the American Bar Association, a 501(c)(6).

Per the ACEP Antitrust Policy, “The College is not organized to and may not play any role in the competitive decisions of its members or their employees, nor in any way restrict competition among members or potential members… There will be no discussions about discouraging entry into or competition in any segment of the health care market.”

Emergency physicians have every right to change this policy to one that aligns with the American Bar Association standards for the sale and ownership of professional practices. In 2023, ACEP took a step in this direction by passing its Corporate Practice of Medicine Policy, which says:

The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) believes the physician-patient relationship is the moral center of medicine. The integrity of this relationship must never be compromised. The physician must have the ability to do what they believe in good faith is in the patient's best interest.

Medical decisions must be made by physicians, and any practice structure that threatens physician autonomy, the patient-physician relationship, or the ability of the physician to place the needs of patients over profits should be opposed. Corporate practice of medicine prohibitions are intended to prevent non-physicians from interfering with or influencing the emergency physician’s professional medical judgment.

The following clinical decisions that impact patient care should only be made by an emergency physician or a nurse practitioner/physician assistant under supervision in accordance with ACEP policy:

Determining what diagnostic tests and treatment options are appropriate for a particular condition.

Determining the need for referrals to, or consultation with, another physician/specialist.

Responsibility for the ultimate management and disposition of the patient.

These decisions, if made by other individuals or entities, would constitute the unlicensed practice of medicine if performed by an unlicensed person. In addition, the following business or management decisions that result in control over the emergency physician’s practice of medicine should only be made by a physician. Under corporate practice of medicine prohibitions, these decisions made as part of the operations and management of an emergency medicine group practice must be made by a physician, physicians, or under the direction of a physician on behalf of the group practice, but not by each individual physician or by an unlicensed person or entity:

Determining how many patients an emergency physician must see or supervise in a given period of time, how many hours an emergency physician must work, or how many hours of coverage are provided.

Determining which patients will be seen by an emergency physician or a physician assistant/nurse practitioner or how such patients seen by a physician assistant/nurse practitioner shall be supervised by an emergency physician.

Selection, hiring/firing (as it relates to clinical competency or proficiency) of emergency physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants.

Setting the parameters under which the practice will enter into contractual relationships with third-party payers.

Oversight of policies and procedures for revenue cycle management, including coding and billing procedures, reimbursement from insurers, and collections for patient care services.

These types of decisions cannot be delegated to a non-physician, including non-physician staff in management service organizations. While a physician may consult with non-physicians in making the business or management decisions described above, the physician must retain the ultimate responsibility for, or approval of, those decisions.

Ownership of medical practices, operating structures, and models should be physician-led and free of corporate influence that impacts the physician-patient relationship. The following types of medical practice ownership and operating structures would likewise constitute the prohibited corporate practice of medicine:

Ownership of an emergency medicine practice or group by non-physician owners or by physicians who do not have responsibility for the management, leadership, and clinical care of the practice.

Restricting access of emergency physicians to information and accountings of billings and collections in their name as described in ACEP’s policy statement “Compensation Arrangements for Emergency Physicians.”

No action has yet been taken to uphold ACEP’s Corporate Practice of Medicine Policy. The ACEP Board of Directors has remained silent on the policy’s enforcement. Again, this silence is a choice, not a legal requirement.

In response to a question on ACEP engagED about physician ownership, ACEP President Aisha Terry, MD, MPH, wrote: “ACEP does not unilaterally make decisions regarding the continued eligibility of membership outside of our bylaws, nor do our policies outline any specific recourse that the organization can take against a company; however, members who have concerns about the behavior of other members can file an ethics complaint, which are always handled seriously.”

It seems unlikely that an American Bar Association President would write such a sentence, leaving their profession’s core practice protections to others. Doesn’t the buck stop with the President?

Lawyers would also prosecute their case. Physicians aiming to increase the likelihood of traditional emergency medicine practices winning hospital contracts will need to find legal advantages over their non-physician-owned competitors.

One such tool is promoting employed physician unionization. Practices owned by their clinicians cannot be unionized. Only employees can form a union.

Unionization would put several levels of strain on a practice not owned by its physicians. Since unions enable collective bargaining, clinicians are likely to receive increased compensation. Per the US Department of the Treasury, “Unions raise the wages of their members by 10 to 15 percent. Unions also improve fringe benefits and workplace procedures such as retirement plans, workplace grievance policies, and predictable scheduling.”

Unions also carry the threat of strikes. Physician strikes are legal as long as they give a ten-day notice of the strike. A strike threat against a contracted emergency medicine practice would be a hospital CEO’s nightmare.

Prosecuting non-physician-owned practices that employ physicians as independent contractors (IC) is another potential tool. By not offering their physicians benefits and labor protections, such employers save significant amounts in labor costs, giving them an unfair advantage over practices that offer benefits. Per Salary.com, benefits comprise 22.8% of employed emergency physician compensation.

The US Department of Labor clarified in 2023 the six elements of independent contractor status. Emergency physicians in a long-term contract with an employer (non-locums) do not meet any of the six criteria. The DOL has also clarified that employees cannot voluntarily renounce their employee status if they meet the legal criteria for being an employee.

TeamHealth, Envision, SCP Health, and ApolloMD employ many or all of their long-term emergency physicians as independent contractors. Legal options to hold those practices accountable for misclassifying emergency physicians as ICs include class action lawsuits, as well as formal complaints to the IRS and the US Department of Labor.

Rulings that TeamHealth, Envision, SCP Health, and ApolloMD are legally required to employ their physicians as W-2 employees would increase their labor costs, lead to financial penalties, and cause agitation within their workforces. All of those results would benefit traditional emergency medicine practices.

As Mark Twain said, “The reports of my death are greatly exaggerated.” Physician-owned traditional emergency medicine practices are not dead yet; they can win more contracts by thinking like lawyers.

Emergency Medicine Workforce Productions is sponsored by Ivy Clinicians - simplifying the emergency medicine job search through transparency.

Dr. Adelman,

Thank you for your recent post about thinking like an attorney. As an attorney and physician, I feel like I must point out one critical fact: you are quoting the ABA model rules. The ABA has no real authority over attorneys -- very similar to ACEP. Now, the ABA lobbies state legislatures to adopt these rules. The model rule becomes state law (or some version of it) if passed by the legislature and signed by the Governor. State law governs behavior regardless of profession.

Skeptical? The ABA has no authority. It’s a political body. It can write model laws and ethics opinions. It can lobby legal and judicial bodies. But actual authority? No. State law and ethics rules promulgated by the state supreme courts govern attorneys. And the mandatory state bar also plays a role. I’m skeptical that anything short of law will curtail the direction medicine has taken (or perhaps has always been depending on your perspective).