Stop Pretending That Professional Fees Alone Can Support Fair EM Salaries

Health systems receive billions in extra government funds to cover the costs of uninsured and underinsured ED care, while emergency medicine practice reimbursements & EM salaries decrease.

Physician Fee Schedule (“professional fee”) reimbursements alone can no longer support fair emergency clinician salaries in the United States.

Medicare, No Surprises Act regulations, and private insurers have systematically decreased emergency medicine (EM) professional fee revenues. Meanwhile, hospital reimbursements have increased with inflation; additionally, hospitals receive extra government payments to cover emergency department care.

The result is a mismatch between hospital and emergency physician practice revenues. Hospitals have a choice: to subsidize their emergency medicine practices or to decrease emergency clinician salaries. Many have chosen the latter, leading to a dramatic 18.8% inflation-adjusted decline in emergency physician compensation over the past five years, per MGMA data.

Health system subsidies to EM practices are rarely discussed openly. Most hospital-based physician practice leaders prefer to keep their subsidies secret to prevent competitors from underbidding their hospital contracts. However, the specialty would benefit from EM leaders moving the discussion of hospital subsidies out of the shadows.

Let’s explore the divergence in emergency care revenues directed to hospitals compared to reimbursements going to emergency medicine physician practices.

A few definitions:

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) defines the Physician Fee Schedule, colloquially referred to as professional fees, as “the primary method of payment for enrolled health care providers. Medicare uses the PFS when paying: a) Professional services of physicians and other health care providers in private practice; b) Services covered incident to physicians’ services (other than certain drugs covered as incident to services); c) Diagnostic tests (other than clinical laboratory tests); d) Radiology services.”

CMS payments to hospitals - generally known as facility fees - are determined through the Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) and the Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS).

Decreasing Emergency Medicine Practice Revenues

Emergency medicine practice reimbursements are being cut by all three primary revenue sources: Medicare, in-network private insurers, and out-of-network private insurers.

According to the American Medical Association, Medicare Physician Fee Schedule payments decreased 29% when adjusted for inflation between 2001 and 2024.

The newly released 2025 CMS Medicare Physician Fee Schedule proposal anticipates a further 2.8% reduction (-5.8% when inflation-adjusted) in physician reimbursement. Anders Gilberg, Senior VP of Government Affairs at the Medical Group Management Association wrote, “CMS has again proposed a negative Medicare physician fee schedule update for 2025 with dangerous implications for beneficiary access to care. A 2.8% reduction to the conversion factor would be alarming in the best circumstances, but to propose doing so at a time when 92% of medical groups report increased operating costs and are otherwise struggling to remain financially viable is critically short-sighted. Medicare physician reimbursement is on a dire trajectory and these ongoing cuts continue to undermine the ability of medical practices to keep their doors open and function effectively — the need for comprehensive reform is paramount.”

In-network negotiated rates for medical services are challenging to obtain. However, available evidence shows that hospitals receive higher reimbursements than physician practices from private insurance when compared with Medicare rates.

According to RAND’s Hospital Price Transparency Study Round 5, which was based on 2022 data, “Prices for facility payments averaged 270 percent of Medicare, and prices for professional services averaged 188 percent.” Since Medicare physician reimbursement rates are falling, a lower private insurance multiplier results in a double-whammy.

When insurers and providers are unable to come to a negotiated agreement on prices, the provider is considered “out-of-network” with the insurer. In a 2020 KFF analysis, 18% of emergency department visits for privately insured patients resulted in at least one out-of-network bill. In 2021, American Physician Partners, one of the fastest-growing acute care practices in the US at the time (and now bankrupt), generated 27% of its clinical revenue through out-of-network payments.

The No Surprises Act changed the process for out-of-network rate setting and payment processing. Starting on January 1, 2024, out-of-network providers would have to navigate a time-consuming, opaque, and expensive process to collect payment for clinical services. An April 2024 study from the Emergency Department Practice Management Association (EDPMA) found the following:

Physician groups experienced a 39% reduction in out-of-network (OON) reimbursement (net collections per ED visit) in 2023 compared to 2021.

Only 33% of eligible OON claims were submitted to the independent dispute resolution (IDR) process. The other 67% of those claims never resulted in an IDR submission. Those claims were paid at rates determined by the insurer.

Only 7.6% of filed disputes have successfully gone through the IDR process to closure.

The average age of disputes in the Independent Dispute Resolution process is 211 days (7 months).

24% of disputes are still not paid or were paid an incorrect amount within 30 calendar days of the IDR entity payment determination, as required by statute and regulation.

In their 2023 bankruptcy documents, both Envision Healthcare and American Physician Partners cite the No Surprises Act implementation as a primary cause of their demise:

“For Envision, the flawed implementation has resulted in hundreds of millions of dollars in underpayments and delayed payments from all health insurance plans.”

American Physician Partners: “Although the legislative policy behind the No Surprises Act is sound, the regulatory implementation of the No Surprises Act was problematic, effectively shifting the balance of power in payment disputes too far in the favor of insurance companies (payors) and enabling them to significantly delay and unilaterally reduce or deny payments.”

Government Subsidies to Hospitals For Providing Emergency Care

Though health systems frequently plead poverty when negotiating with physician practices, the evidence appears otherwise. As with any market, some companies are financially stronger than others.

When considering hospital finances, it is important to note that a plurality are not-for-profit. A US Department of Health and Human Services 2023 study found that “nearly half of the 4,644 Medicare-enrolled hospitals are non-profit (49.2 percent), 36.1 percent are for-profit, and 14.7 percent are government-owned.”

An analysis from the Hospitalogy newsletter from June 2024 concluded:

“Most large health systems performed better in Q1 2024 when compared to the first quarter of 2023.

And if you’ve followed Hospitalogy writings over the past year, it’s pretty easy to see why: utilization is up, the labor market has stabilized, and dense health system consolidators are staying ahead of the game.…

Several players – including Tenet, Baylor, Mayo, AdventHealth, Providence, and Ascension – saw significant improvement in operating margins between the two periods. Baylor sitting at 8.7% in Q1 is particularly unreal performance. The Dallas-based nonprofit is benefiting from strong Texas markets and strong strategic decision-making within.”

Kaufman Hall’s July 2024 National Hospital Flash Report concluded that “May data show signs of stability.” The US hospital median year-to-date operating margin was 3.8%.

Part of the reason hospital finances are generally stable is that health systems receive large amounts of extra funding to provide 24-7 emergency care. The American Hospital Association (AHA) graphic below clearly uses ED care as justification for extra payments in the form of outpatient facility fees:

Health systems receive the following bonus payments to cover the costs of providing 24-7 acute patient care. Independent physician practices rarely or never receive these extra payments.

Facility fees paid to hospital outpatient departments.

When medical practices that had previously only billed professional fees are sold to health systems, the newly consolidated practice can bill both a professional fee and a facility. They do this despite only changing ownership rather than the services delivered.

A Health Affairs article, “Facility Fees 101: What is all the Fuss About?”, summarizes: “One component of provider pricing growing in prominence is hospitals charging ‘facility fees’ for care provided in outpatient and physician office settings that hospitals own or control. These fees are ostensibly overhead charges, but for the hospitals and health systems that own these practice settings; the fees are not necessarily intended to cover costs specific to the setting or the patient being charged. Facility fee charges are becoming more common as hospital systems have accelerated their purchase of ambulatory settings and practices, leading to higher overall costs for outpatient care. Consumers bear the brunt of this, as they face increased out-of-pocket costs as well as higher premiums from these extra charges. Consumer exposure to these fees, coupled with the fact that these fees often appear unrelated to the level of care received, is contributing to the growing public perception that provider prices are too high.”

Federal Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) Allotments.

According to Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), the US government paid hospitals $15.0 Billion in 2022 in extra Medicaid DSH payments to compensate hospitals for treating uninsured and underinsured patients.

KFF defines DSH payments as follows: “Disproportionate Share Hospital adjustment payments provide additional help to those hospitals that serve a significantly disproportionate number of low-income patients; eligible hospitals are referred to as DSH hospitals. States receive an annual DSH allotment to cover the costs of DSH hospitals that provide care to low-income patients that are not paid by other payers, such as Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) or other health insurance. This annual allotment is calculated by law and includes requirements to ensure that the DSH payments to individual DSH hospitals are not higher than these actual uncompensated costs.”

Upper Payment Limit (UPL) supplements.

In 2022, hospitals received more from UPL payments - $15.8 Billion - than from DSH payments. Like DSH supplements, UPL is designed to help hospitals cover the costs of care for uninsured and underinsured patients.

The Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission explains, “UPL payments are lump-sum payments that are intended to cover the difference between FFS base payments and the amount that Medicare would have paid for the same service. FFS and UPL payments for services cannot exceed a reasonable estimate of what would have been paid to a class of providers, in the aggregate, according to Medicare payment principles. Classes of providers are defined based on ownership (i.e., government, non-state government, and privately owned). States can use a variety of methods to estimate what Medicare would have paid, including a payment-based method (i.e., based on the hospital’s aggregate Medicare payments relative to its charges) or a cost-based method (i.e., the hospital’s costs according to Medicare cost principles).”

Uncompensated Care Pools.

Hospitals receive further government funds—$10.0 billion in 2022—to cover the costs of treating uninsured and underinsured patients through uncompensated care pools.

According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, “Some State Medicaid agencies operate uncompensated care pools (UCPs) under waivers approved by CMS. Section 1115 of Title XIX of the Social Security Act gives CMS authority to approve experimental, pilot, or demonstration projects that it considers likely to help promote the objectives of the Medicaid program. The purpose of these projects, which give States additional flexibility to design and improve their programs, is to demonstrate and evaluate State-specific policy approaches to better serve Medicaid populations. To implement a State demonstration project, States must comply with the special terms and conditions (STCs) of the agreement between CMS and the State. The purpose of the UCPs is to pay providers for uncompensated cost incurred in caring for low-income (Medicaid and uninsured) patients. Through UCPs, States pay out hundreds of millions of dollars to providers and receive Federal financial participation.”

The 340B Drug Pricing Program.

The 340B Program allows health systems that treat large numbers of low-income patients to purchase outpatient drugs at significantly reduced prices. Eligible entities can then charge market rates for administering those medications, leading to increased profits.

A 2021 study found, “Total 340B sales at the 340B price approached $30 billion in 2019 and continue to grow rapidly. We estimate that in 2019, 340B created over $40 billion in profits which were shared between covered entities [including hospitals], contract pharmacies, and possibly patients (in the form of reduced-price medicines).”

Current State of Hospital Subsidies To Emergency Medicine Practices

Some of the funds hospitals receive to care for emergency department patients, the uninsured, and the underinsured reach EM practices in the form of hospital subsidies. Due to the secretive nature of these subsidy payments, details are tough to find. The analysis below summarizes the little that is publicly available on the topic.

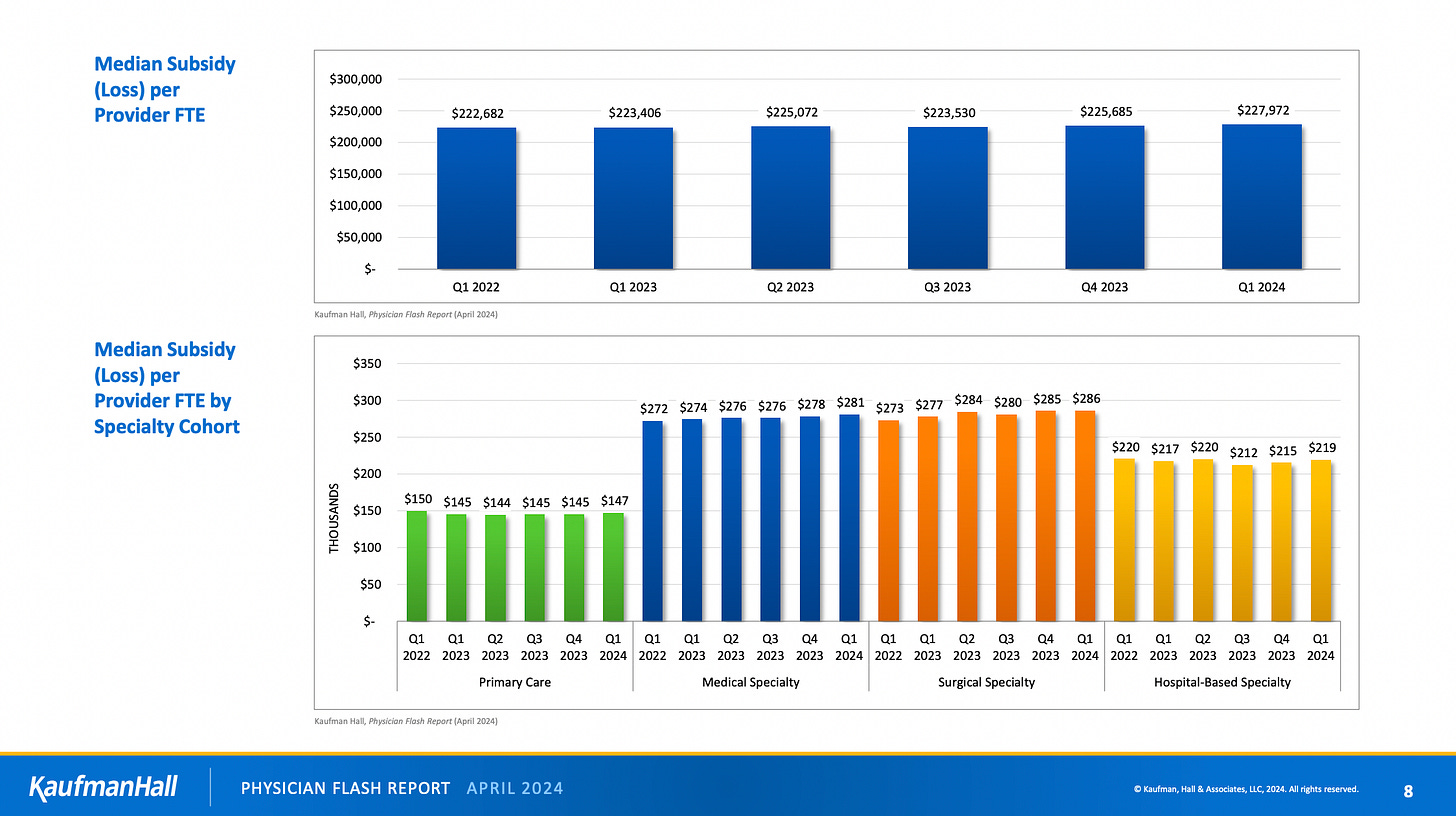

Kaufman Hall, a healthcare management consulting company, publishes a quarterly analysis of aggregated health system-employed physicians and their practice financial data. Kaufman Hall combines emergency medicine data with other hospital-based specialties.

Kaufman Hall’s analyses have consistently shown large financial losses for hospital-based specialties. In the April 2024 publication, the median net patient revenue per provider FTE was $250,000 per year, while the median total expense per provider FTE was $469,000 per year. That translates to a 87.6% net loss.

These sizable losses (subsidies) for physician practices were echoed in 2023 earnings calls by HCA Healthcare and Community Health Systems (CHS) after in-housing some of their physician practices following the bankruptcies of Envision and American Physician Partners. Kevin Hammons, CHS’ President and Chief Financial Officer, said on the Q3 2023 earnings call, “When factoring in the net revenue associated with in-sourcing those physicians, we estimate we benefited by approximately $4 million sequentially compared to the subsidy payments previously paid to APP.”

Fierce Healthcare’s article about HCA’s Q3 2023 earnings call is titled “HCA Healthcare's newly consolidated physician staffing venture is bleeding $50M per quarter, execs tell investors.” The article continues, “During Tuesday morning's quarterly investor call, HCA Chief Financial Officer Bill Rutherford said that the [physician practice] venture had a roughly $100 million negative impact on the company's third quarter and year-to-date adjusted EBITDA.”

Partners in the law firm Foley & Lardner LLP discussed “Subsidy Arrangements Between Hospitals and Physician Practices” on the Healthcare Law Today Podcast in July 2023. Pertinent parts of the discussion include:

“What specialties do we normally see that received this financial assistance? Anesthesia, emergency medicine, hospitalist, critical care, and trauma surgery, just to name a few , but generally your hospital-based specialties are most likely to receive a subsidy. Of course, there are many reasons for that. The primary one being that professional collections generally don’t cover the costs of the practice.…

One of the things I didn’t blink or think twice about frankly - I have been dealing with subsidies during my career, which is 20 plus years - in the emergency medicine space because it’s a 24/7 concept and it’s a difficult line of business to manage effectively from a staffing perspective. It’s needed, right? You can’t operate without your emergency department if you’re a typical hospital, shall we say. Then some of those practices because of EMTALA concerns, because they are treating any patient or stabilizing patients that come through the door, there is frequently a gap in exactly what you said in that cost issue. The practice has to cover the cost for the staffing, they’ve got to cover the cost to have the people there to do it, and it amounts to, or results in a much more, shall I say, intimate relationship from a financial perspective between the practice and the hospital or health system.”

Outsourced hospital-based physician practices are generally tight-lipped about their subsidy arrangements. Even American Physician Partners’ notorious 2021 fundraising slide deck did not disclose hospital subsidy details.

A comparator to note: according to Coker, a prominent healthcare consultancy, “From an economic standpoint, anesthesiology groups are increasingly dependent on hospital support to ensure market-based wages that are needed to attract and retain high-quality anesthesia providers. According to various studies, 85 to 95 percent of all hospitals directly or indirectly subsidize their anesthesia services.”

Future State of Hospital Subsidies To Emergency Medicine Practices

Why are the tens of billions of government dollars earmarked for emergency department care of the uninsured and underinsured not reaching emergency physicians, PAs, and nurse practitioners?

The 2024 MGMA Provider Compensation and Productivity Report, based on a survey of medical practices that employ more than 211,000 physicians and advanced practice providers, showed a harsh reality for emergency medicine. Emergency physician compensation (inflation-adjusted) decreased by 18.8% over the past five years, the most of any specialty surveyed.

That decrease in compensation stands in stark contrast to the billions of dollars hospitals and health systems receive to provide EMTALA-mandated care. As detailed above, those funds come through various programs:

Hospital Outpatient Facility Fees;

Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) Allotments;

Upper Payment Limit Supplements;

Uncompensated Care Pools;

340B Drug Pricing.

Just as hospital payments are not limited to facility fees, EM practice payments should not be limited to professional fees. Time for hospitals to openly share the government funds intended for emergency department care with those who dedicate their careers to expertly delivering that ED care - emergency physicians, PAs, and nurse practitioners.

Acknowledgement: Thank you to Jason Adler, MD, CEDC, for his help on this article. Check out Jason’s July 2024 ACEPNow piece, “Financial Headwinds Cause Hospital Subsidies to Rise.”

Emergency Medicine Workforce Productions is sponsored by Ivy Clinicians - simplifying the emergency medicine job search through transparency.

even more true if hospitals bill, and reimburse phhysicians for service in ER. However if you are employed by an. ER Contract group you are out of luck. Hospitals rarely employ physicians directly..They are too smart for that