Residency Unions Are Winning Improved Contracts

Committee of Interns & Residents (CIR), US' largest house staff union, has won big raises and improved working conditions at dozens of residencies. Attendings can learn from trainees' successes.

The Committee of Interns and Residents (CIR), the US' largest house staff union, has used collective bargaining to win significant raises and improved working conditions at dozens of residencies across the country.

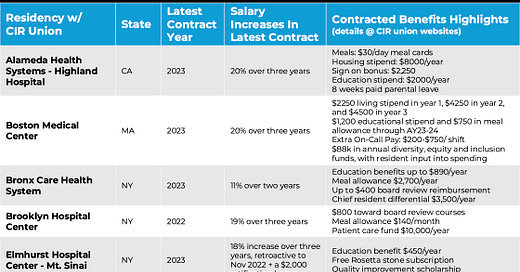

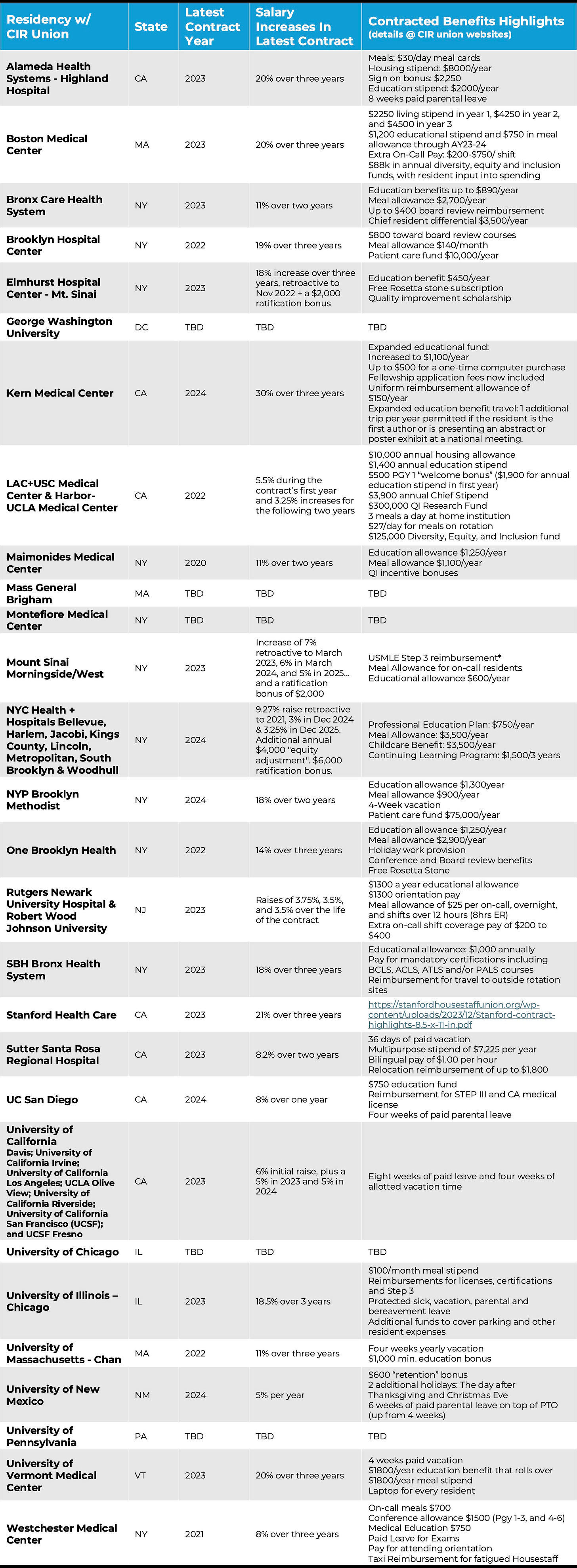

CIR’s wins have been paired with rapid growth. Recent additions include the training programs at Mass General Brigham, the University of Pennsylvania, Stanford Health Care, and George Washington University. CIR now represents 33,000 residents and fellows. See the chart below for a summary of residency contracts negotiated by CIR over the past three years.

For example, Stanford interns who start in 2025 will make over $100,000 as a result of successful CIR negotiations.

According to a CIR statement in December 2023, “Resident physicians and fellows at Stanford Health Care reached a groundbreaking agreement on their first contract with the health system, which includes a 21% increase in compensation, preservation of essential departmental benefits, a $50,000 annual stipend for a resident wellness committee, fully-funded rideshare services for fatigue mitigation, and a new grievance and arbitration process, will profoundly impact their lives and their ability to provide exceptional care to their community.”

At New York City’s public hospitals, residents represented by CIR negotiated sizable raises this year after extensive negotiations. Per The City Report on May 29, 2024, “The Health + Hospitals Corporation, which operates the city’s eleven public hospitals, and the union representing about 2,300 resident physicians reached a tentative six-year agreement. The deal gives an immediate 9.27% raise retroactive to 2021 and then adds 3% in December followed by 3.25% in December 2025. Those raises would put their salaries on par with peers at private safety-net hospitals, according to the union, plus an ‘equity adjustment’ ranging from $1,131 for more experienced residents to $4,000 for those in their first three years to bring starting salaries up to more than $76,000. The residents will also receive ratification bonuses upon signing of up to $6,000. For current first-year residents, the deal would amount to a nearly 23% raise by the end of next year.”

Resident physicians have traditionally been willing to work long hours at meager wages as part of an implicit agreement with the broader US healthcare system. Early-stage physicians would work like crazy for almost nothing for three to seven years after medical school. In return, physicians who complete the grueling path would receive a meaningful career with professional respect, practice autonomy, and lifelong financial security.

However, now that health insurers have decreased reimbursements, medical school costs have ballooned, and most medical practices have been bought out by health systems or private equity, the deal's fairness has broken down. In response, residents are negotiating for fairer early-career compensation.

Without a union, resident physicians have little power to negotiate for improved working conditions. Changing residency jobs is challenging and nearly impossible except at the July 1 residency start date. Meanwhile, because the number of US residency spots is kept below the level of demand, replacing a resident is usually not difficult for residency programs.

Unions give residents power through one main mechanism: the threat of collectively withholding their labor. Residents’ work is essentially irreplaceable at academic medical centers. The most effective way to show something’s value is to demonstrate what life would be like without it.

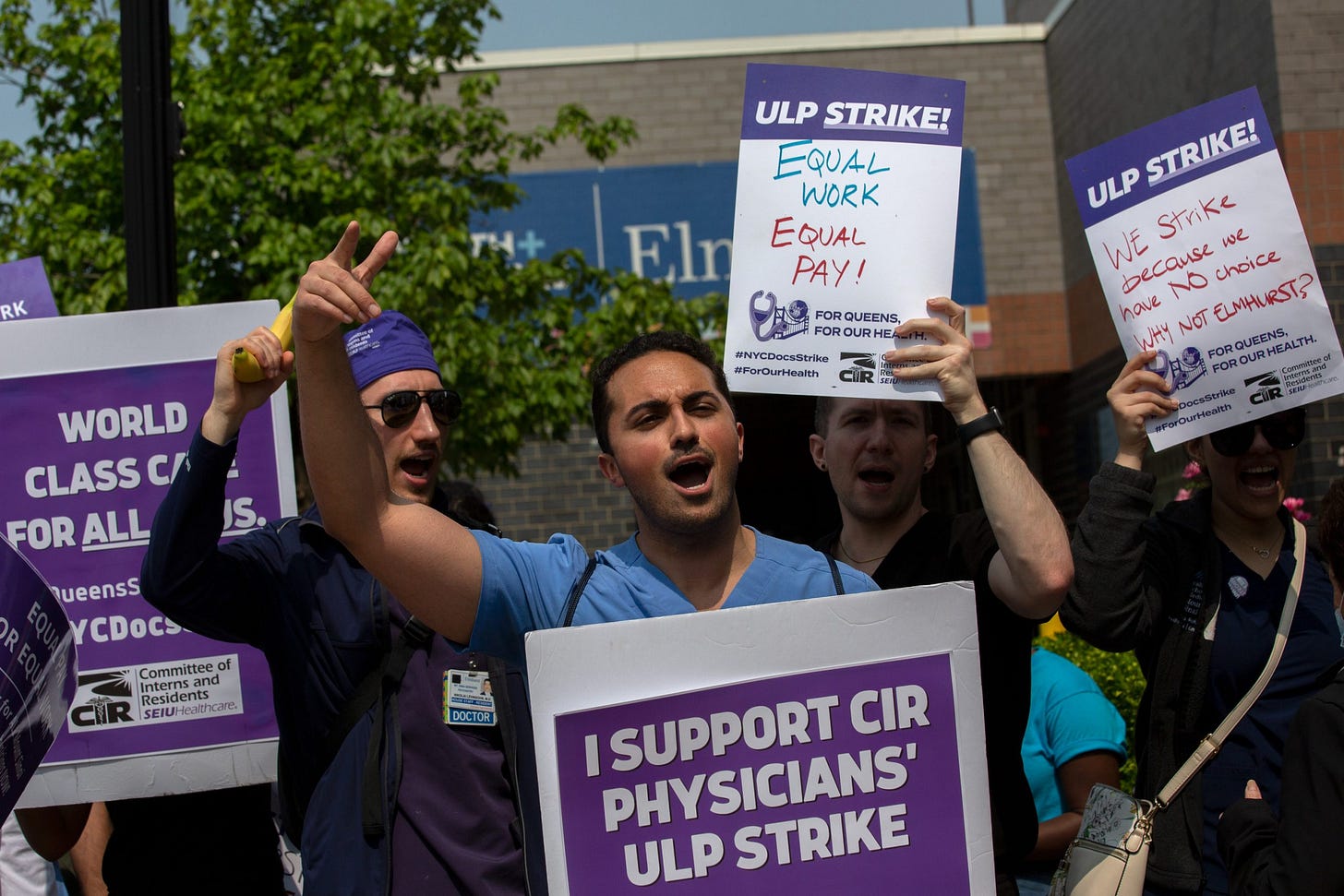

The May 2023 resident strike at NYC Health + Hospitals / Elmhurst in Queens, NY, was an example of a motivated resident union using its power to negotiate contract improvements.

As documented in this New York Times piece, Elmhurst was at the epicenter of the first COVID wave in the US. Despite risking their lives in harrowing working conditions during the pandemic, Elmhurst residents—employed by Mount Sinai Health System—were paid $7,000 per year less than their colleagues at Mount Sinai’s flagship private Manhattan campus. The Elmhurst residents also did not receive any hazard pay from their pandemic work.

According to a CIR statement before the strike, “While bargaining consistently in bad faith, Mount Sinai continues to refuse to bring the physicians’ salaries up to parity with Mount Sinai Hospital residents or to agree to hazard pay language for the doctors who brought Queens through the worst of COVID… ‘It feels so unjust that we, as largely immigrant doctors serving this working-class immigrant community in Queens, have to beg to get what we need to pay our rent, and from a corporation like Mount Sinai that touts its commitment to New York communities,’ said Dr. Tanathun Kajornsakchai. ‘Mount Sinai should invest in the doctors caring for so many people in Queens who cannot get care anywhere else.’”

After the three-day strike, Mount Sinai Health System agreed to Elmhurst resident wage increases of 18% over three years, retroactive to November 2022, a $2000 ratification bonus, an enforceable agreement to negotiate on hazard pay, a meal allowance that reaches parity with Mount Sinai Hospital residents, chief differential pay of $3500, holiday pay, and ACGME leave.

The New England Journal of Medicine article, “Hospital Consolidation and Physician Unionization,” by Kevin Schulman, M.D. and Barak Richman, J.D., Ph.D., explains that physician unions can negotiate over two sets of priorities.

“The first is the opportunity to negotiate over wages with monopolists. By definition, a monopolist employer (or, more precisely, a single purchaser, or monopsonist, of labor) will set wages at subcompetitive levels. Employers with a unionized workforce, however, are under a legal obligation to negotiate in good faith with union representatives. This obligation explains why workers in industries dominated by a single employer, such as sports leagues, often choose to form unions. Without the National Football League (NFL) Players Association, for example, the NFL could set below-market wages, and the world’s best football players would have little bargaining recourse. The National Basketball Players Association has negotiated over “collective revenue,” and the new National Basketball Association (NBA) collective bargaining agreement ensures that the players collectively will receive 51% of the league’s basketball-related income. Contrary to popular belief, collective bargaining is intended to bring order — not chaotic threats of work stoppages — to management–labor relationships, which helps explain why previous physician strikes have had no discernable effect on health care outcomes.

The second opportunity offered by unions involves the ability to voice concerns about and influence organizational governance. Unions often express workers’ concerns about non–wage-related matters, including issues affecting job satisfaction, professional meaning, and workplace conditions. Only a fraction of the NBA’s collective bargaining agreement’s 676 pages concern compensation. The NFL Players Association regularly holds teams accountable for player safety, training-room resources, and other nonmonetary concerns. The Air Line Pilots Association advocates for aviation safety at an industry level and addresses operational performance issues affecting individual airlines. Governance matters are a primary concern for many U.S. physicians who are grappling with new challenges regarding staffing, clinical care workflows, functionality of electronic health record systems, and patient care resources, but who find that their ability to address any of these issues is limited.”

A reasonable question, then, is why more than three-quarters of US residencies are not represented by a union. The most compelling explanation is federal and state legal restrictions. The 1947 Taft-Hartley Act enabled states to pass “right-to-work” legislation. In “right-to-work” states, employees can benefit from a union’s negotiated contract without joining the union or paying dues. In other words, the right to work translates to a right to freeload, making union organizing difficult. More than half of US states have right-to-work laws.

Another disincentive to unionize is the cost. The CIR’s fees are 1.5%. Union dues are a key reason workplaces where employees feel well-treated and appropriately compensated rarely unionize.

In a 2024 American Medical Association interview, Dayna Isaacs, MD, MPH, an internal medicine resident at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), discussed her perception of CIR’s fees: “We received a 6% salary increase followed by two years of 5% increases in our latest contract, plus a $1,200 educational stipend per year, so we got much more back than we put in. To me, it’s a very wise investment in the greater good. By paying our dues, we're able to achieve a lot for ourselves, our patients and the hospital generally.”

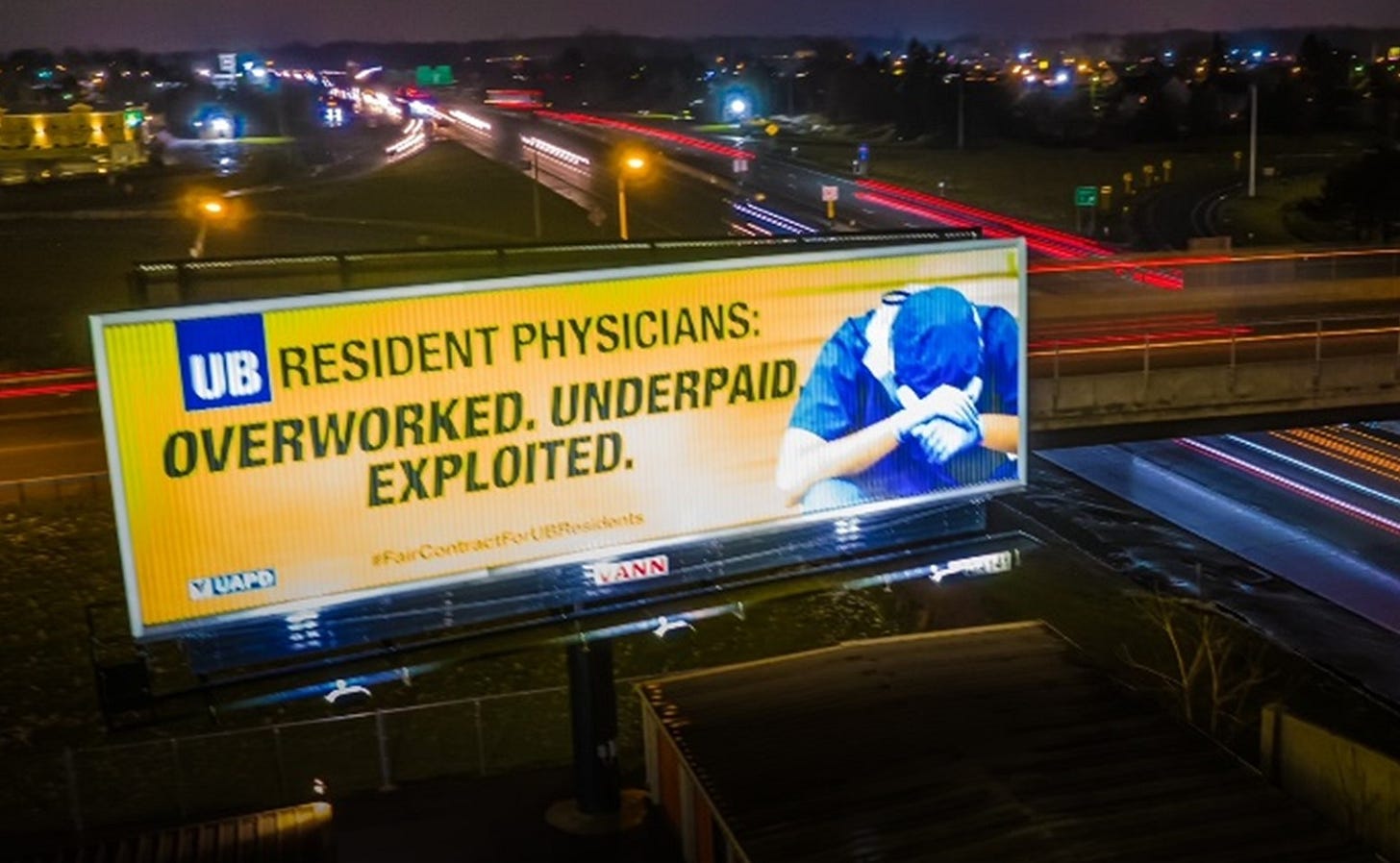

The next test of resident union power will likely be in Buffalo, NY. The University at Buffalo has been playing rope-a-dope with the UB House Staff Union, a Union of American Physicians & Dentists (UAPD) member. Both the University at Buffalo’s hospitals and the Jacobs School of Medicine representatives have said they do not have the authority to negotiate with the union. Instead they referred the union to a shell company - University Medical Resident Services, Inc. - which the UB residents say has not negotiated in good faith.

After over a year of failed negotiations, the union and its 830 residents have set a strike date for September 3, 2024. “The UB medical residents remain the lowest paid in New York State, the only residents without retirement benefits in the region, the only residents without a training stipend in the region, and now, have the poorest healthcare policy in the region,” according to a union statement.

“We will not be bullied anymore. We are taking a stand for ourselves and for our patients,” said Dr. Armin Tadayyon, an anesthesiology resident and member of the UB House Staff Union’s bargaining team.

Emergency Medicine Workforce Productions is sponsored by Ivy Clinicians - simplifying the emergency medicine job search through transparency.