Mandating 4-Yr Residency is Good for Hospitals, Not for Emergency Physicians

The ACGME has proposed adding a year to emergency medicine residency training. Health systems will make millions from extra government payments and increased cheap resident labor.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), responsible for accrediting physician training programs in the US, has proposed requiring all emergency medicine (EM) residencies to be four years long. Currently, 80% of EM residencies are three-year programs.

The ACGME’s rationale is based on its opinion that emergency physicians need more training. Check out the slides below from the ACGME’s Emergency Medicine Program Requirement Revision Preview Webinar, posted on February 11, 2025.

The assertion that recent EM residency graduates provide “inefficient” and “less competent” care is presented in the ACGME webinar without evidence. In contrast, studies have shown that graduates of four-year EM programs perform equivalently to their three-year residency graduate peers. The following is from the ACEP Council Resolution, “Supporting 3-Year and 4-Year Emergency Medicine Residency Program Accreditation,” adopted in 2023.

WHEREAS, Emergency Medicine residencies have included three-year and four-year programs since the 1980s; and

WHEREAS, A 2023 ABEM study published in JACEP Open compared ACGME Milestones data and ABEM test performance of emergency physicians completing three- and four-year residencies concluded the “results do not provide sufficient evidence to make a confident determination of the superiority of one training duration compared with the other”; and

WHEREAS, A 2023 study in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine utilized data from over one million patient encounters by three-year graduates, four-year graduates, and experienced new hires found similar performance on “measures of clinical care and practice patterns related to efficiency, safety, and flow” among the three groups; ultimately concluded the results did not support recommending one length of training over the other; and

WHEREAS, There is no clear evidence from existing literature that either three- or four-year programs are superior or noninferior to the other; and

WHEREAS, Any change to length of training requirements in emergency medicine should be evidence-based; therefore be it

RESOLVED, That ACEP recognizes the value of choice in emergency medicine residency training formats and supports the continued accreditation of both three-year and four-year emergency medicine residency programs.

If the evidence does not show that four-year EM residencies are superior to three-year programs, why would the ACGME require the more extended training option? Since residents are overworked and underpaid, wouldn’t the shorter three-year training duration be preferred?

When things do not seem to make sense, the answer is often money. Let’s dive into the financial incentives involved in the proposed ACGME requirement for four-year EM residencies.

Three-Year EM Residencies Break Even WITHOUT Government Graduate Medical Education Subsidies

In “The Effect of Emergency Medicine Residents on Clinical Efficiency and Staffing Requirements”, Jeffrey Clinkscales, MD, et al studied the financial impact of starting the EM Residency at the University of Tennessee College of Medicine Chattanooga, which launched in 2008. At the time, the residency was a joint venture among the University of Tennessee College of Medicine Chattanooga, the Erlanger Health System, and EmCare Inc.

The study found that the increase in emergency medicine attending physician productivity due to working with EM residents resulted in financial benefits equivalent to the costs of operating the residency. Importantly, this calculation did not include government Graduate Medical Education (GME) subsidies to the hospital.

According to Clinkscales, “The annual operating cost of the EM residency program in 2013, including academic teaching and administrative services; support staff; and resident salaries, benefits, and other costs, was $1,821,108. By implementing a residency program, the ED saved an estimated 4,860 hours of attending physician coverage and 5,828 hours of MLP coverage per year. This represents an estimated $1,741,265 of saved clinical staffing cost in 2013, which is comparable to the cost of the residency program. In addition, the observed 5% increase in RVUs billed per patient represents an estimated $340,519 of billable services in 2013 and may have resulted from improved documentation, an increase in the number of procedures performed in the ED, or other changes attributable to the residency program.”

Government GME Funding Makes EM Residencies Profitable

Medicare and Medicaid pay hospitals to train resident physicians in addition to the patient care revenue generated by those programs. Per the New England Journal of Medicine article, “The Economics of Graduate Medical Education,” “Total federal GME funding amounts to nearly $16 billion annually. Medicare is the largest federal government contributor to GME, providing $9.5 billion — almost $3 billion for direct medical education (DME), to pay the salaries of residents and supervising physicians, and about $6.5 billion for indirect medical education (IME), to subsidize the higher costs that hospitals incur when they run training programs. Federal Medicaid spending adds another $2 billion for GME, and an additional $4 billion comes from the Veterans Health Administration and the Health Resources and Services Administration. States support GME through nearly $4 billion in Medicaid spending.”

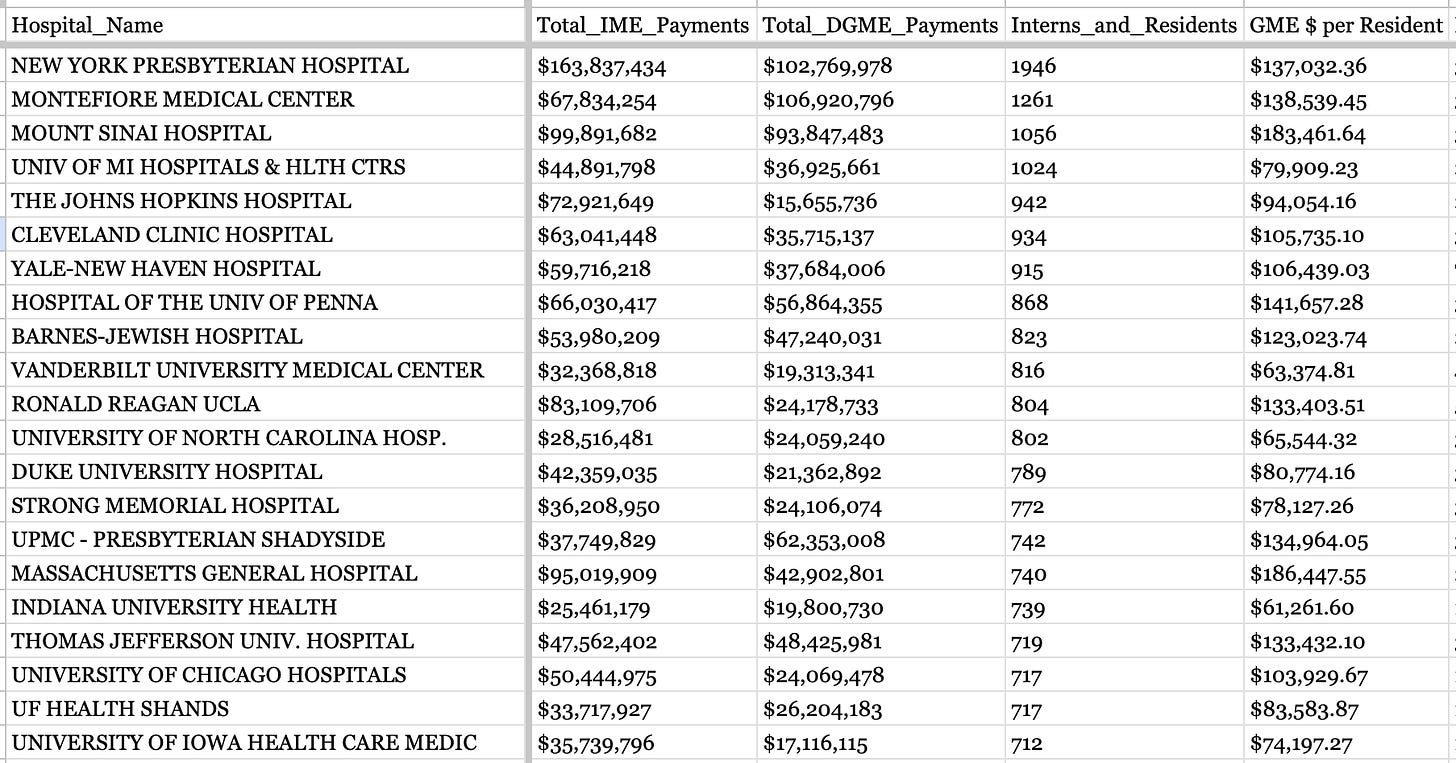

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) releases Medicare GME funding data by hospital. The following chart lists 2023 Medicare GME payments to the largest residency training hospitals.

Medicare GME payments per resident are similar between for-profit and non-profit health systems. A JAMA article by Kushal Kadakia, MSc et al. summarizes, “For-profit hospitals’ participation in GME has increased substantially over the past decade, with $832.8 million in federal subsidies allocated in 2020. Program sizes and hospital teaching intensity were similar between for-profit hospitals and nonprofit hospitals. These findings suggest that the health care industry increasingly values GME as an asset rather than a money-losing endeavor.”

Medicaid GME payments to hospitals vary significantly by state. New York funds GME most generously, at $1,919,000,000 in 2022. Alabama, Alaska, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Rhode Island, and Wyoming did not make Medicaid payments for GME in 2022.

The No Surprises Act added yet another GME-related financial benefit for teaching hospitals. Federal Independent Dispute Resolution (IDR) arbitrators are instructed to incorporate “the teaching status, case mix, and scope of services of the facility that furnished the qualified IDR item or service” when considering appropriate insurer payment rates.

The profitability of emergency medicine residencies has incentivized a rapid increase in the number of EM training programs in the US. According to David Carlberg, MD, “EM postgraduate year-1 (PGY-1) positions increased from 2,056 to 2,840 (38%) between 2014 and 2021. Emergency medicine had the largest growth rate of PGY-1 positions among all medical specialties from 2014 to 2019, growing twice as fast as the overall number of residency positions across specialties. While many of these additional residency positions resulted from new programs opening, the expansion and contraction of established programs led to the creation of an estimated 129 additional EM PGY-1 positions from 2018 to 2022. Roughly 70 programs expanded while 13 contracted. The number of EM residency programs increased from 222 to 273 (23%) between 2014 and 2021 after accounting for the single accreditation system (SAS). An average of nine new EM residency programs opened annually from 2016 to 2021, while an average of four programs opened annually between 1983 and 2015. Many of the new programs founded between 2013 and 2020 opened in states with a plethora of established programs. The number of programs in Florida nearly quadrupled (from 5 to 19), and the number of programs in Michigan and Ohio at least doubled (11 to 25 and 9 to 18, respectively).”

Adding a Cohort of Fourth-Year EM Residents Would Improve Residencies’ Profitability

Not surprisingly, EM residents become increasingly productive and efficient as their training progresses. In “Productivity and Efficiency Growth During Emergency Medicine Residency Training”, Matthew Singh, MD et al. quantify residents’ operational improvements over the course of a three-year residency. The study finds that “resident productivity and efficiency improve over the course of residency training. Similar to the findings of previous research, productivity as measured by number of patients seen per hour appears to advance more quickly and reach a plateau by the PGY2 year. However, efficiency as measured by door-to-decision time improves over the course of training.”

The compensation difference between a fourth-year resident and a first-year attending physician is dramatic. According to Medscape, the average fourth-year resident physician earned $70,000 per year in 2024. Meanwhile, the average attending emergency physician was paid $379,000 annually. The difference is even more stark when considering that residents work significantly more hours per week than attending emergency physicians.

Those familiar with Medicare GME policy have raised Medicare caps as a potential limiting factor to prolonged EM residencies’ revenue generation. However, this is a misunderstanding of how Medicare GME caps are calculated.

Medicare provides Graduate Medical Education funding to academic hospitals for each resident physician based on the length of their Initial Residency Period (IRP). The number of Medicare-funded years depends on the resident's ACGME-determined specialty training duration. If the ACGME converts the EM residency duration from three years to four, the hospital will receive Medicare GME payments for residents completing that extra year. The total number of residents in the program would be expected to increase proportionately with the added year.

The Bottom Line

Three-year emergency medicine residencies are financially self-sufficient without federal funding.

Government GME payments contribute an extra ~$200,000 per resident per year, making EM residencies profitable for hospitals.

Adding a cohort of fourth-year EM residents would significantly increase total resident productivity while decreasing health systems’ labor expenses.

If three-year emergency medicine residencies have been financial winners for hospitals, four-year EM programs will be even better for them! For the doctors who are stuck doing an extra year of residency - without evidence that the fourth year will make them better emergency physicians and being paid $300,000 per year less than they would as attendings - not so much.

Notes:

PS: The specialty of emergency medicine really can’t afford to be even less desirable to high-achieving medical students. Check out the 2024 NRMP Match data from Brian Carmody, MD's excellent Sheriff of Sodium blog.

Emergency Medicine Workforce Productions is sponsored by Ivy Clinicians - simplifying the emergency medicine job search through transparency.

Thank you for this. I authored the study you included to demonstrate the profitability of EM residencies. Your analysis is spot-on, and I share many of your concerns about the proposal. When I was doing this research as a resident a decade ago, there was a steady drumbeat from ACEP and national EM leaders warning of a dire shortage of EM doctors. In my naïveté, I assumed that the goal of these calls was to expand the number of EM-trained physicians. I thought that proving that residents were profitable would help. I didn’t suspect until I came to publish that the real goal was to pressure the government to expand GME funding. The howls of outrage when the number of EM programs expanded without GME funding seemed to confirm the matter. Whatever the truth concerning the quality of EM education (into which I claim no special insight), some of the proposal’s support surely stems from its potential to achieve the long-sought federal money - with the added bonus of coming at the relative expense of the newly-arrived competition. While many of the concerns about resident education are, no doubt, genuine, couching self-interest in those terms would be a maneuver with long historic precedent. We ought to be clear-eyed about our motivations. And the benefit to resident education, if it is there, ought to be demonstrated, not assumed.

Great comments all, but the discussion begs a major question that lies at the root of this conundrum. MISSION CREEP. What happened to the “Emergency” in emergency medicine ? As an old school dual trained/certified IM/EM graduate myself , I feel compelled to ask obvious but overlooked dimension in this discussion to wit , Why is our speciality involved in addiction medicine /consulting/ follow up at all ?telemedicine ? Even observation medicine? Smoking cessation programs ? Even critical care ? Would any of my colleagues argue we don’t have too much to do already taking care of core emergencies ? We should be resuscitating and stabilizing patients, not delivering extended critical care. We should be ruling out life and limb threatening situations, not providing data for long term precise diagnoses or facilitating longitudinal care for chronic illness. These should be handled in appropriate cost effective venues under the purview of OTHER specialities. Critical care beyond the first hour should in the controlled , staff defined, more longitudinal environment of an ICU or in the OR. Hospitals are not only exploiting the GME game detailed here,but they are shifting work that logically should be handled as in patients by in patient services OR outpatients in clinic. Our original sin is we allowed ourselves to be all things to all patient and administrators. This stems from our 24 hour availability, the broad interests of most emergency physicians (I am a poster child in this regard) ,and even professional insecurity ….but our leadership failed to envision the longer strategic game (again another trait of emergency physicians) of controlling Our own specialty rather than let it be defined by hospital administrators and other specialities selecting offloading work they should be doing by training and expertise, but eschew for convenience and financial reasons. This is a unique vulnerability of our speciality and deserves much more attention and action. Concomitant to any discussion about expanding training periods is a equally intentional discussion of LIMITING our scope of practice, and thus need for extended training. It’s already out of control. We can’t expect other specialities and administrators to NOT exploit our 24 hour a day presence, intellectual curiosity , and selflessness . Any speciality calling itself a speciality has to control their scope of practice, and thus training requirements. We need to stop going around looking for more things to do, more relevance to hospital administrators. Decades into our development, we still project ourselves as the 7-11 of medicine. We have only to look to ourselves in this regard. We have been complacent and passive, and in many cases naive or even causative. Don’t look just to the stars, dear Brutus.