ACEP ED Accreditation: A Line in the Sand & A Hidden Gem (Part 2)

With ED Accreditation, ACEP incentivizes physician-led ED patient care and defines core elements of high-performing emergency medicine practices.

(Note: the previous EM Workforce Newsletter post explored the 30 elements required for a hospital to receive ACEP ED Accreditation.)

The ACEP ED Accreditation criteria aim to spur more hospitals to deliver physician-led emergency department care. This goal aligns with ACEP’s 2023 policy statement: “The American College of Emergency Physicians believes that regardless of where a patient lives, all patients who present to emergency departments deserve to have access to high-quality, patient-centric care delivered by emergency physician-led care teams.”

As emergency department visits are expensive and high-risk, most patients want to be seen by expert clinicians with verified skills in managing emergency patient care.

Per a 2022 Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) analysis, “large employer plan enrollees’ emergency department visits cost $2,453, on average, with enrollees responsible for $646 in out-of-pocket costs.” Four-fifths of that amount are facility fees (payment to the hospital), and one-fifth are professional fees (payment to clinicians). Costs vary based on ED visit complexity, as seen in the KFF chart below.

In other words, the cost in the US of an average ED visit for a patient with commercial health insurance is the equivalent of 752 tall Starbucks lattes.

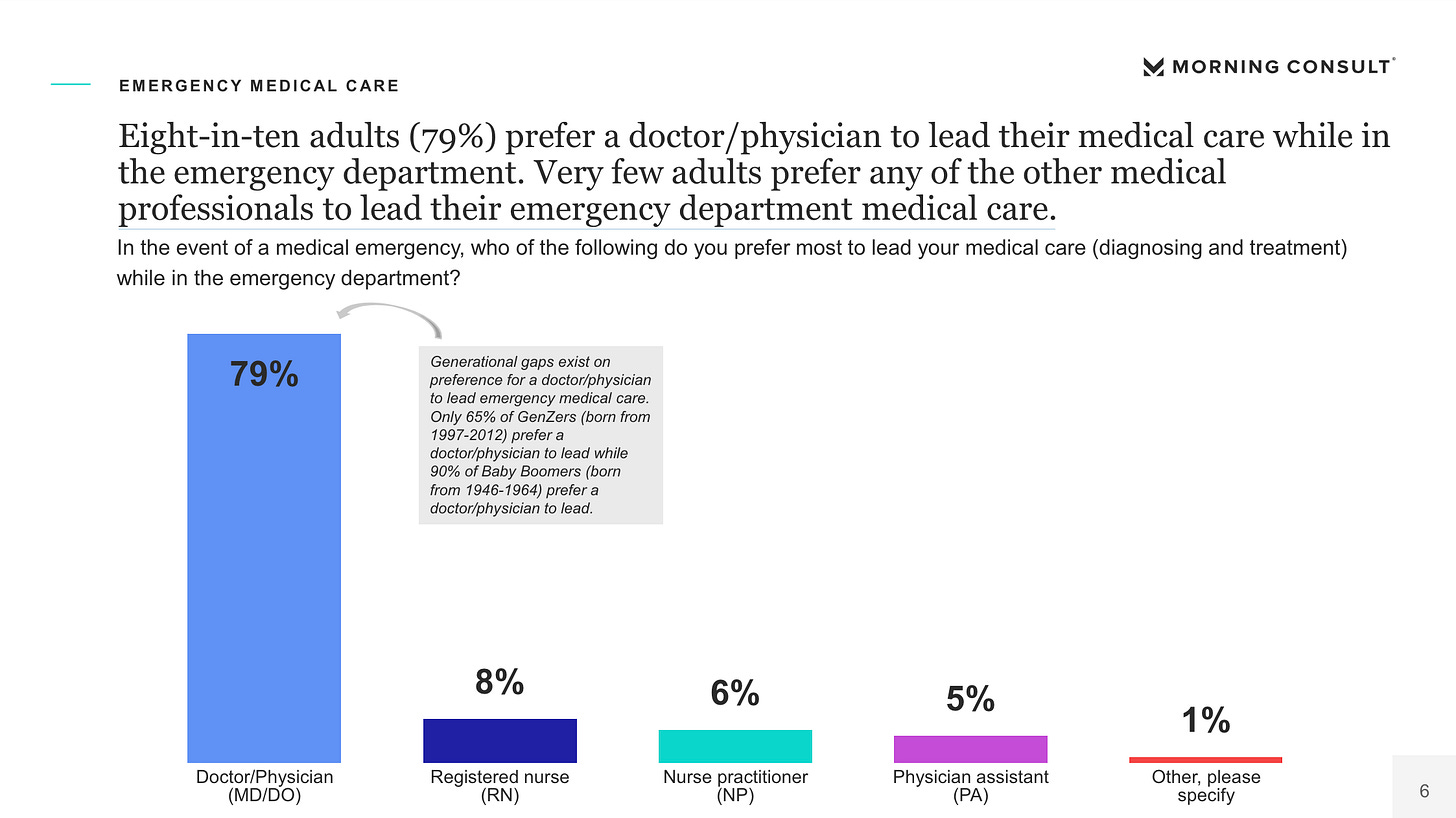

When asked who they wanted to lead their emergency department visits, most patients choose physicians over those with less training. According to a 2022 Morning Consult poll of 2209 adults, “Eight in ten adults (79%) prefer a doctor/physician to lead their medical care while in the emergency department. Very few adults prefer any of the other medical professionals to lead their emergency department medical care.”

In line with these findings, ACEP ED Accreditation’s Gold and Silver levels require an emergency physician's real-time involvement in every ED patient's care.

This requirement faces significant operational, financial, and workforce-level challenges. One might ask, does a board-certified emergency physician need to see every low-acuity ED patient? This concern aligns with the results of a 2021 ACEP survey of 2200 adults, which found differences in the percentage of patients who preferred to see a physician based on the severity of their ailments (see image below).

It is unclear whether the current emergency medicine workforce can support the requirement for every ED patient to see an emergency physician. This is especially true in rural settings. As Gettel et al. found, “emergency physicians comprise less than half of the rural emergency medicine workforce, initially representing 51.3% in 2013 and decreasing to 46.4% of all clinicians serving rural designations in 2019. Conversely, advanced practice providers’ market share increased from representing 23.0% of rural clinicians in 2013 to 32.7% in 2019.”

The financial barriers to increasing ED physician staffing are significant. According to Medscape, the average annual emergency physician income is $352,000, while the average physician assistant compensation is $139,000 per year. Of note, efficiency gains from AI-enhanced ambient documentation technologies may affect the emergency medicine skill mix’s financial calculations in the future.

To account for EDs’ operational and financial challenges, ACEP Accreditation includes a bronze tier, which says: “Low Acuity (e.g., ESI levels 4 and 5) patients may be seen by a qualified NP or PA who will consult an emergency physician as needed.” Per ACEP, “the tiered system aims to allow any ED to obtain at least a level 3 accreditation easily, while Level 1 and 2 sites involve more significant investments.”

A concerning omission in the ACEP ED Accreditation criteria is the lack of a provision for PAs and nurse practitioners to achieve greater levels of autonomy with increased emergency medicine training and experience. PAs and NPs dedicated to attaining high levels of knowledge and skills in emergency medicine can deliver excellent acute patient care.

The NCCPA Certification of Added Qualification (CAQ) in emergency medicine is an example of such a qualification program. Per the NCCPA, “PAs seeking the Emergency Medicine CAQ must demonstrate they have advanced knowledge and experience in emergency medicine, above and beyond that expected of entry-level PAs or PAs working in a generalist practice. PAs seeking eligibility for the Emergency Medicine Specialty Examination must meet requirements of specialty-specific CME and experience in the field.”

Tucked into the ED Accreditation document’s last page (p. 15) is a section titled “Blue Ribbon Recognition.” This section may prove to be the most impactful accreditation element.

Emergency medicine practices are often tough to differentiate due to a lack of meaningful descriptive criteria available to clinicians. To illustrate this point, a few questions that show the difficulty in differentiating core working condition elements:

What are the differences in due process procedures between USACS and Vituity?

Do Wake Emergency Physicians (WEPPA), Middle Tennessee Emergency Physicians (MTEP), or members of the Independent Emergency Physicians Consortium (IEPC) offer all of their full-time emergency physicians predefined and reasonably achievable pathways to partnership?

Does TeamHealth include non-compete agreements in its physician contracts?

Without accessible criteria to evaluate EM practices’ working conditions, clinicians cannot be expected to make informed career decisions. Groups’ incentives to provide their clinicians with the best possible working conditions decrease when prospective employees cannot see such differentiating factors.

The ACEP ED Accreditation program takes an important step in defining the elements of high-performing emergency medicine groups. It also allows clinicians to identify which employers meet those standards. Blue Ribbon practice accreditation requires the following standards:

Due process for emergency physicians regardless of employment/contractual arrangements.

Contracts with the EPs, including both hospital and contracting group, do not include a restrictive covenant (non-compete).

Medical staff credentialing and privileging forms do not include questions regarding prior psychiatric care, unless impacting work performance.

Emergency physicians have the right to view itemized reports of what is billed and collected for their service at least semi-annually.

To learn more about the ACEP Emergency Department Accreditation program, head to https://www.acep.org/edap.

Emergency Medicine Workforce Productions is sponsored by Ivy Clinicians - simplifying the emergency medicine job search through transparency.